What vitalizes them is the friction of the characters’ incongruent desires: on the one hand, to embrace the simplicity of someone else’s authority on the other, to assert their own authorship. All sex, of course, is psychological, but the source of the charge here is more than just a dom-sub mind game. These scenes both do and do not seem like ordinary kink.

All she truly wants is someone (by implication him, or maybe Him) to tell her “what to wear every morning,” to instruct her on “what to like, what to hate, what to rage about . . . what to believe in . . . how to live my life.”

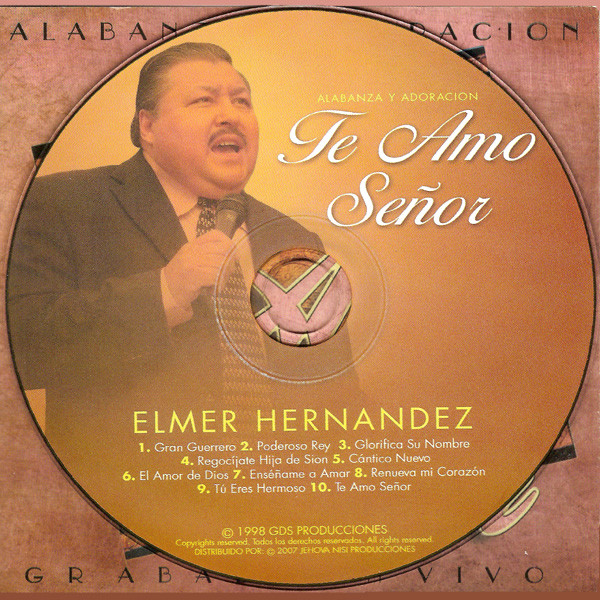

#Gloria popkey elmer series#

It’s also in the second season of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s TV series “ Fleabag,” when Fleabag confesses-literally-to the priest she lusts after. And in Rooney’s “ Normal People,” when Marianne discloses to gentle, sensitive Connell, her on-again-off-again boyfriend, that another man has hit her with a belt, choked her-that she asked for it, enjoyed it. It’s in Sally Rooney’s “ Conversations with Friends,” when Frances tries unsuccessfully to get Nick-older, married, kind-to choke and hit her during sex. I’d seen it crop up recently in widely praised works both written by and featuring brazen, outspoken, and almost always middle-class white women. This contrast-of women raring to assert their agency in one context, then willing, even eager, to relinquish it another-captured my interest in part because of its familiarity. She would never have known to ask for it. There were no choices to make.” She liked it. “The whole time he was watching me,” she reveals to her audience of other mothers, “I didn’t have to do anything. When she twitches, he says, “Don’t fucking move.” Maybe twenty minutes pass before he orders her to get up. He pushes her, fully clothed, face-first onto the bed, then sets one hand on her back and one on her neck and presses down. The hotel is where they spend their first night together. She is twenty-“an adult,” she makes explicit, if still a college student-when she begins an affair with a married professor in his early forties.

She recites it with a dramatic sense of remove with time, the narrative has accrued significance, like rust on iron left in the damp. This time, it is the narrator who holds forth, carefully unfurling her own story. Divorced and living with her young son in California, the narrator has assembled a group of other single mothers.

He is exactly the kind of partner a liberated woman is supposed to want, and yet she despises him for it. Of the intervening years, we have learned that she married and abruptly divorced a kale-loving man, a classmate in her grad-school cohort, whom she describes as “nice” and “ever so understanding.” She is mocking him. Toward the middle of the book, some fourteen years after this Italian vacation, the same disparity crops up once more-but here it’s the narrator who internalizes it. It’s the vast disparity, the deep conflict, between Artemisia’s desire for absolute narrative control and her desire for sexual submission. But, instead of fear, it was appreciation and relief that overwhelmed her: appreciation because he had restored to their relationship the power hierarchy that she preferred, relief because she had been “released from control.” This is a startling opening scene, but what startles most is not, as one might expect, the husband’s display of brutality. The word she does use is “violence.” Her husband showed her his strength, pushing her against the wall, one hand on her shoulder, one on her neck. The story’s dénouement may or may not warrant the label of rape. The narrator, mesmerized by the older woman’s poise, the conviction of her self-knowledge, listens but barely speaks.Īrtemisia’s story is about power: who has it and why, how it animates and shapes desire. Prompted by a bottle of wine, a pack of cigarettes, and the narrator’s talk of a recent breakup, she is soon recounting the events that hastened the collapse of an earlier marriage.

One evening, after the children are asleep, their mother, Artemisia, a formidable psychoanalyst who was born in Argentina, joins the narrator on the hotel terrace. The unnamed narrator, twenty-one and set to begin graduate coursework in the fall, has been brought along on a wealthy friend’s family vacation. Miranda Popkey’s début novel, “ Topics of Conversation,” opens in Italy, in 2000. Miranda Popkey’s protagonist reckons with “the folly of governing narratives.” Photograph by Elena Seibert

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)